People often assume that I’m the founder of ZA’AKAH because since assuming its directorship in December of 2016 I’ve become such a public face for it, but the truth is that when ZA’AKAH first started I didn’t support its aims. ZA’AKAH was started by 5 Footsteps members who were use that name to organize a protest the Internet Asifah in 2012, an event planned by a wide array of Charedi community leaders for the purpose of declaring the internet banned. The event was planned for May in Citi Field, where the Mets play baseball, and was going to include many speeches by Gedoilim, many of whom would be in attendance both from the Chassidish and Litvish worlds.

The ZA’AKAH organizers felt that if the community was going to spend so many millions of dollars on something as asinine as banning the internet, they could and should devote at least some of that to helping survivors of sexual abuse access justice and resources to help them heal. The Orthodox community is notorious for denying that the community is suffering an epidemic of sexual abuse, and equally notorious for retaliating against community members who dare to report fellow community members for sexual abuse. To be clear, sexual abuse is not a uniquely Orthodox problem, but the manner in which the community goes about silencing survivors and punishing those who speak out is unparalleled in the broader Jewish community.

It is still the stated policy of many in the Charedi community to require permission from a rabbi before reporting sexual abuse to secular authorities, and even when such permission is granted survivors still face the threat of backlash for reporting. Survivors regularly lose access to jobs, schools, marriage prospects, and community standing for speaking out publicly, and risk other severe consequences. Resources for survivors are almost nonexistent, and most survivors find that their abusers have ready access to full-throated public support from rabbis and community leaders than they do.

Against this backdrop, the ZA’AKAH organizers sought to point out the hypocrisy of the community in declaring all-out war on the internet while doing nothing about the issue of sexual violence. For my part I was skeptical about the comparison. I was still very much part of the community, Charedi in my outlook and observance, and I didn’t see why a community couldn’t hold two values simultaneously: That the internet was a pernicious spiritual threat, and that sexual violence was a scourge that must be dealt with properly. Contrasting the two made no sense to me. I commended the organizers for organizing, but urged them to do something more productive with their time. Being that I was a 20 year old pisher who knew nothing about the real world at the time, they humored me and carried on.

A month or so before the Asifa I walked out of my office in Boro Park and saw a sign on a lamppost advertising a fundraiser for Nechemya Weberman, a former unlicensed therapist in Satmar Williamsburg who had been arrested (and was since convicted) for repeatedly raping a 12 year old client of his. Incensed at this brazen and disgusting public display of support for a pedophile I called one of the ZA’AKAH founders and suggested that if they wanted to do something actually productive they should organize a protest outside the fundraiser.

Despite that call taking place the day before the fundraiser, they managed to organize a very successful protest outside which called national attention to what was happening in the case. They then continued with the Asifa protest as planned. That protest was much smaller than the Weberman protest, but it got good press coverage nonetheless, and continued ZA’AKAH’s momentum. Not believing in the logic behind the Asifa protest I didn’t attend. I now regret that decision.

As I got older and more involved in advocacy on behalf of survivors of sexual violence in the Jewish community, eventually assuming the directorship of ZA’AKAH, I began to better understand the thought behind the Asifa protest. As the years went by, I saw how some of the worst people in the community were publicly supported without question. I saw rapist after rapist, pedophile after pedophile, provided with the best lawyers money could buy while their survivors drank, drugged, binged, purged, starved, hurt, and killed themselves to make the pain go away. I spent countless hours on the phone with survivors who were losing their homes, jobs, families, communities, marriages, children, sanity, health, and futures while the people who caused their suffering were honored at dinners, defended by rabbis, and supported by fellow community members.

My heart broke over and over again as I told survivor after survivor that I couldn’t help pay for their therapy, even though I didn’t know if they’d be alive long enough for treatment to be expensive, that I couldn’t provide them with access to justice because the rabbis they grew up revering were fighting and paying to make sure that never happened. I had no answer when survivors asked me why no resources were available for them when heaven and earth moved whenever a crook or abuser in their community asked it to.

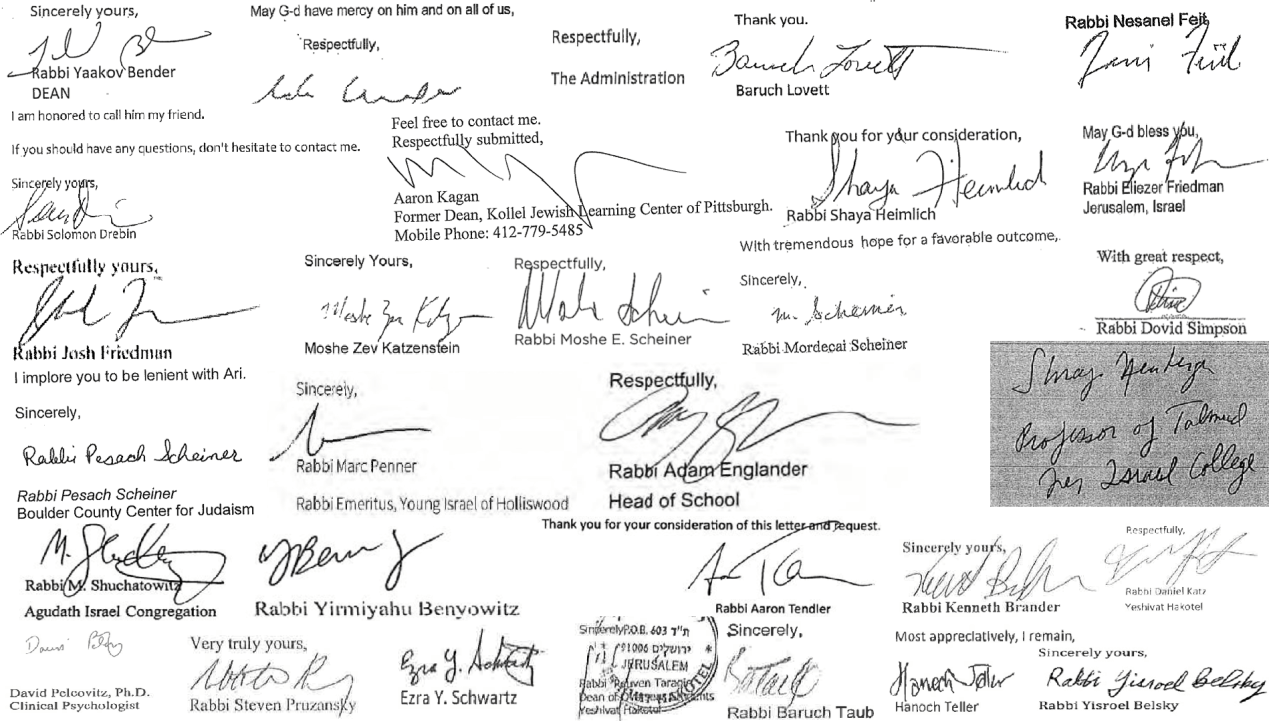

And then I started reading letters written by rabbis on behalf of convicted pedophiles, rapists, and abusers, rabbis I knew in many cases had had a personal hand in either covering up the abuse in that case or in other cases. That’s when I understood what animated the original ZA’AKAH organizers to protest the Internet Asifa: Is it possible for a community to hold two priorities at once? Sure. But a community whose priorities are so focused on minute stupidities would never be able to focus on the real problems. A community spending millions to ban the internet would never take the issue of sexual violence seriously because they were spending so much time focusing on such a stupid problem.

If the internet was to them such a big problem that it was worth spending millions, and millions of dollars, and who knows how many man-hours gathering together every Charedi community within a 100-mile radius to hear speeches about how evil it was, then they would never care about sexual abuse. They were demonstrating their priorities clearly and emphatically, telling anyone who would listen to them, that they didn’t see anything else as worthy of attention.

That’s what writing a letter on behalf of a pedophile, rapist, or sexual abuser says to the community: That you just don’t care about the issue. Is it possible to care about the wellbeing of people convicted of crimes and facing incarceration as well as the wellbeing of those who suffer sexual violence? In theory. In practice, however, when no expense is spared to help the abusers, and no resources are available to help the victims, the message to survivors is very clear: You are an inconvenience at best, a blemish at worst, and we would much prefer if you left, died, or stayed silent forever.

It’s so rare for rabbis to publicly support survivors that if such instances exist, they can be counted on one hand. It’s so common for rabbis to publicly support abusers that it’s impossible to recall all the examples.

Consistently, abusers can count on the best representation in court, whether civil or criminal, including appeals, support for their families in the rare instances they incur judgments or are sentenced to prison, rabbis telling their communities not to talk about it because it’s lashon hara to discuss abuse cases, and the presumption of innocence or teshuva, even post-conviction, even if there’s no evidence of either. Survivors, on the other hand, can expect nothing but vitriol or callous indifference.

So sure, when we have a community where rabbis truly understand the experiences of survivors, speak out publicly against abusers, write public letters of support on behalf of survivors being mistreated by their communities, publicly raise funds for the mental health, legal, and material needs of survivors, create safe communities oriented around best-practices based abuse prevention and response policies designed to keep children in the community safe and protected, when survivors can assume that they’ll be believed, protected, supported, and healed, when abusers legitimately fear punishment for their crimes – then we can talk about whether or not it’s ok for rabbis to write letters for pedophiles, rapists, and abusers. Something tells me that once we’ve accomplished all that, whichever rabbis are left will think better of it if asked.