The second day of the Krawatsky trial began with the second alleged victim being called to the stand by Jon Little. He was accompanied by his service dog, Maisie. The second alleged victim is currently 15 years old.

He began by saying that he went to Shoresh and did not have a good time. He didn’t remember how his initial contact with Krawatsky came about, but remembers Krawatsky being there as a counselor and identified him in the courtroom. He said he was at Shoresh for 2014 and 2015 and wasn’t excited to return the second year but doesn’t remember why.

After summer of 2014 he says he remembers having outbursts and starting to wet the bed again. He said he went back in 2015 and describes an incident where he was in a bathroom stall urinating and Krawatsky walked in wearing swim trunks, pulled them down exposing his penis, and then offered the second alleged victim $100 to touch his penis. He said he remembered no other incidents with Krawatsky.

He said he remembered seeing his then-therapist but doesn’t remember if he saw him before Shoresh. He said he knew the first alleged victim’s mother by name but not personally, and that he knows the first alleged victim but hasn’t seen him in a very long time. He said he remembers one session with his therapist and the first alleged victim, but doesn’t remember discussing what happened at camp with the first alleged victim, his therapist, or the first alleged victim’s mother, and also doesn’t recall talking to CPS about the case.

He did, however, say he remembered being given gifts by Krawatsky. Little then produced a ceramic plate and showed it to him. He recognized the exhibit as having been given to him by Krawatsky after a ceramics class at camp where he didn’t like the dish he’d made, and Krawatsky gave him a a plate instead. The plate said “Rabbi K” on it, and the second alleged victim said he didn’t write that there himself.

Benjamin Kurtz then rose to cross-examine him. His demeanor, as always, was combative.

Kurtz started by asking him if he was alone by the pool area where the alleged abuse happened. He said yes. Kurtz asked him if the first alleged victim was there, and he said he didn’t remember. Kurtz then started badgering him about what happened to him, asking if he remembered his prior depositions, if he remembers the first alleged victim being there with him, if he ever saw him being violated. He said he remembered the depositions but didn’t remember any details about the first alleged victim.

Kurtz then asked him if he remembered being raped repeatedly (which is not what he testified to on direct examination), and he said he didn’t remember being raped, repeatedly or otherwise.

Kurtz then moved in to ask him about the statement he made about Krawatsky pulling his pants down in the locker room, asking him if that testimony was the first time he mentioned that fact. He said that he didn’t think so. When Kurtz asked him when else he said it, he said he thought in one of the previous depositions.

Kurtz then showed him a deposition to refresh his recollection. After reading it Kurtz asked him if he now remembered saying that, and he said that yes, he just remembered having said it. Kurtz asked him if he had just remembered that day for the first time that Krawatsky was naked, to which Little objected and was sustained.

Kurtz then asked if it true he denied being touched from 2015-2016. That was objected to as well and the objection was sustained. Kurtz then asked if he recalled his parents and CPS talking to him in 2015, and if he remembered how he made his disclosure. He said he didn’t remember. Kurtz then asked about how often he talks about the allegations with other people, and he answered that he only talked about it in depositions, and maybe once with his therapist.

After cross examination, Little redirected to ask him to look at the deposition and see if he was ever asked about Krawatsky being naked. He answered no.

Little then called the father of the second alleged victim. The father is a well educated, well-spoken, affable person. He described choosing Shoresh because they knew some people who sent their kids there, and from the promos they saw it looked like a good place. Asked about why he sent his kids to an Orthodox camp when he and his family aren’t, he said that he liked what he saw with Shoresh and didn’t mind his kids seeing the other side.

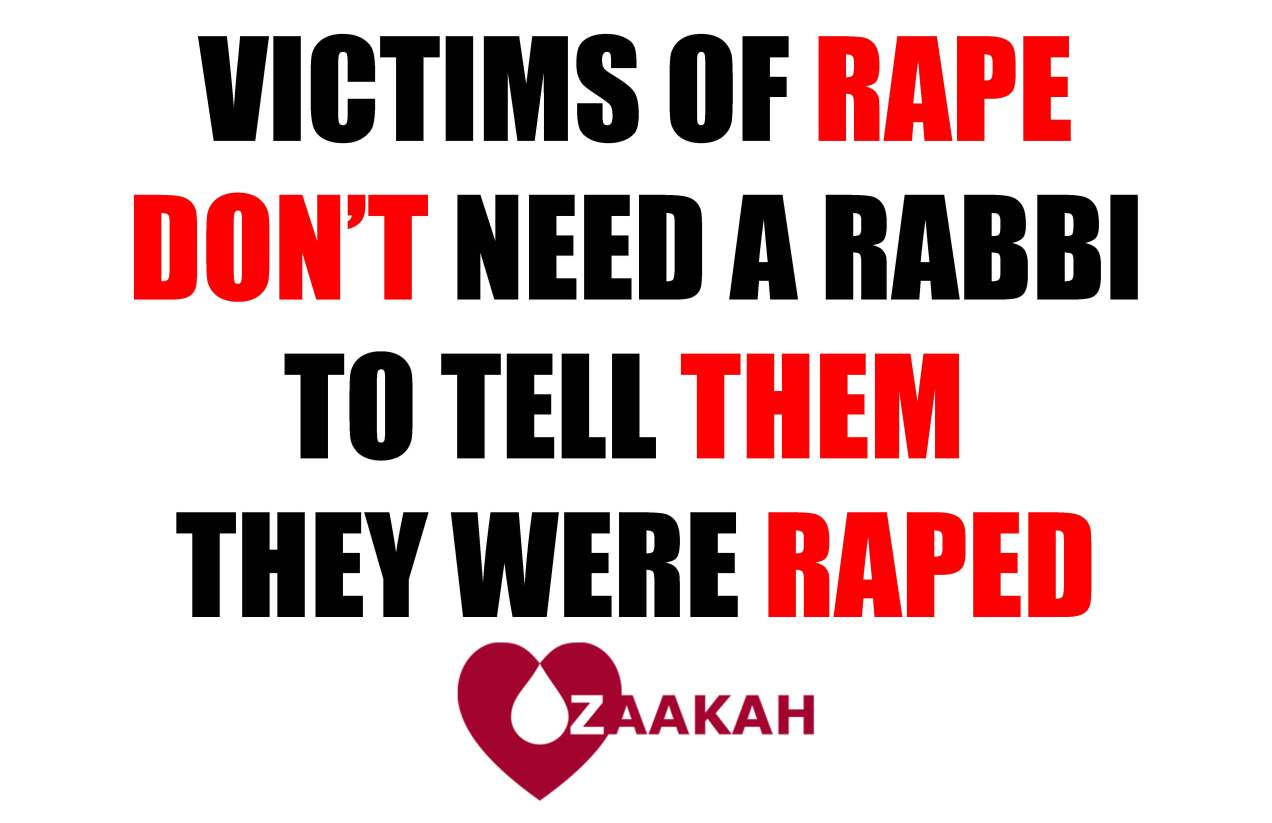

He talked a little about the Orthodox community in general, saying that they tend to consult with rabbis more about both personal and legal matters, and feel it’s more important to prioritize Jewish law over secular law. He was asked if Orthodox Jews would consult with a rabbi before going to authorities, but that was objected to and the objection was sustained.

Talking about his son’s behavioral issues he said that his son had had some behavioral issues before Shoresh, and he suspected his son had ADHD because his other child did too, and sometimes he didn’t want to do assignments, but that everything got much worse after Shoresh, more explosive, in a way it never was prior. He discussed a specific instance in 2015 when they were discussing which camps the kids would go to and he told his son he’d be going back to Shoresh, a few days later the school called him to tell him his son was having an episode, being rude to teachers, and disruptive, which is when he noticed the shift in behavior.

He said his son didn’t say what was going on, but they put him in therapy, and he started ADHD meds. For the first three weeks his son was back in Shoresh, he said, his wife was working in the camp at the time so perhaps there were small issues he wasn’t made aware of because she could resolve them, but he wasn’t made aware of any issues. Then after 3 weeks, he said, they started noticing bedwetting, soiling the pants during the day, avoiding public spaces, and refusing to walk into any locker rooms even at other pools at friends’ houses.

He said his son attended the second month of Shoresh but was expelled two weeks in after being carried over to his mother by a staff member (Krawatsky) following a fight with another camper. He described Rabbi Dave Finkelstein calling after the expulsion to express concern and offer help, which he said he appreciated at first.

After session ended, right before CPS called him, Rabbi Dave called him again on his cell. CPS then called the next day to schedule a meeting to talk with him and is son. He said he scheduled the meeting for the following week after a planned trip with the family. On that trip he said that his son refused to go into any of the public bathrooms when the stopped and that he’d rather soil himself than use one. He said his son used the bathroom at the hotel, and wet the bed a bit, but absolutely refused to use any public bathrooms.

After returning, he said, they met with CPS in their home where they asked his son if Krawatsky had offered him money to touch his penis. The father said they weren’t prepared for such questions because he’d been given the impression by Rabbi Dave during the second call the night before CPS called that they’d be calling about an incident of physical violence with another child. He said that was the first time they heard about anything sexual happening.

After the meeting with CPS, he said, Rabbi Dave tried calling multiple times, as well as his son’s counselor calling several times. They didn’t pick up either of them. During his second cal with Rabbi Dave he’d gotten the impression that there was an issue with another kid, but he only figured out which kid after the father of the first alleged victim reached out to him on LinkedIn, trying to connect. The two were in the same industry so they had a lot of professional overlap.

The two spoke a few times by phone and finally met at the first CPS hearing where his son was still saying nothing happened. Following that hearing the two decided that they should have both their kids, who seemed to have been affected at camp, do something together. They proposed the idea to the second alleged victim’s therapist, and the therapist reached out to CPS and police to help decide if and how to make it happen.

They finally decided on the first supervised playdate at the therapist’s office to be held on November 22, 2015. The two kids were in the room with the therapist observing them. The first alleged victim’s mother was not present. He said they learned nothing from that first playdate so they arranged a second for a week or so later. The same people were present, he said, the session was recorded, and in that session the therapist asked him to go in and sit inside during the session. He said the therapist told him that he’d picked up on two things that indicate abuse happened.

He said the conversation between him and the therapist following the playdate was recorded, and following that conversation the therapist explained what happened to the father of the first alleged victim. The mother of the first alleged victim, who was at the office but not inside the playdate, asked if she could talk to the second alleged victim to try and get him to open up. He said that at first the therapist didn’t like that idea since he didn’t see the value, but she insisted, and the father of the second alleged victim agreed to let her talk to him just in case it helped.

He said he watched her talking to his son. He said she was intense, but not yelling, perhaps raised her voice, but he didn’t feel his son was afraid, intimidated, or scared of her. He said they spoke for less than 5 minutes. He said the discussion was not recorded.

After that he said he spoke with the first alleged victims’ mother a couple of times in person at their house, at dinner, and two CPS hearings, and on the phone about 10-15 times. He said he spoke to the first alleged victim’s father a little more, mainly by phone but also at industry conferences they both attended, mostly not about the abuse though.

He was asked to give his thoughts on Lashon Hara and explained it means evil speaking, saying bad things about someone that aren’t correct, and defaming him.

Asked why he wanted the initial CPS meeting with his son at their house and not at a Child Advocacy Center (CAC) he said that they offered both options and his son had an appointment with his doctor that morning so home was easier.

He was then cross examined by Benjamin Kurtz.

Kurtz began by asking him about his wife’s employment at Shoresh. The father said his wife worked there the whole time his kids were at Shoresh. He said his son had attended Shoresh in 2013 as well but that there had been no outbursts prior to 2014.

Then Kurtz started doing his Kurtz thing again of being combative with parents of alleged victims. Kurtz asked him about an incident involving his son flipping a piece of furniture over in school, which led to the classroom being cleared. He said he didn’t remember the particulars. Kurtz then asked him if his son was expelled for violence, and he said he didn’t know the exact reason.

Kurtz asked him how he didn’t know if his wife worked there, and he said he knows it was something between his son and another kid, that he hit him or fought or something. Kurtz sarcastically asked him about the incident he didn’t remember if his kid flipped a desk and if it happened in March 2014. He said no. Kurtz then asked him what did happen in March of 2014, and he said that he got a call from his son’s teacher saying his son was refusing to do assignments and being rude to the teacher.

Kurtz asked him to confirm that this was before he had any incidents with Rabbi K, and he said yes. Kurtz asked him if that incident at school necessitated him coming to get his son during the day, and he said no, he just had to come see the teacher after school, that the room wasn’t cleared and his son wasn’t kicked out.

He said that in 2015, after camp, is when the incident happened at school that necessitated the room being cleared.

Kurtz then started asking him why he didn’t know why his son was kicked out of camp, asking if any of his other kids had ever been kicked out of camp and whether it was disturbing to find out his son had been. He said that none of his kids had been kicked out before and that is was disturbing to find that out. Kurtz then asked why he didn’t ask why his kid was kicked out of camp, and he said he probably did, he just doesn’t remember now, but he remembers it being related to fighting with a kid.

Kurtz then asked him about the first CPS meeting with his kid, slipping in a snide remark about the father feeling free to wait a week to take his family on vacation before scheduling it, asking how many times they asked about the abuse. He said 4 or 5. Kurtz asked if his son denied it, and he said that his son had said he didn’t remember anything.

Moving on to the video of the playdate at the therapist’s office, Kurtz asked him if his son was led by the first alleged victim to say anything. That was objected to and sustained. Kurtz then tried to get him to say his son had denied the allegations in that room, and he insisted that he never said that, and that his son had just said he didn’t remember.

Kurtz then asked him essentially if at that point, after talking to CPS, police, and the first alleged victim’s parents, he decided to just make a disclosure happen because his son wasn’t saying anything. That annoyed the father and he said that he wouldn’t say that, the therapist was also trying to figure out why his son’s behavior had changed.

Kurtz asked him if the therapist orchestrated the meeting, and he said that it may have come about because the parents of the first alleged victim suggested it, but that the therapist is the one who made it happen.

Kurtz then started asking him about the involvement of CPS and police in organizing the playdates, showing him emails and asking him if he saw CPS or police people’s email addresses on them. When the father said no, Kurtz asked him if he himself had ever communicated with them about the playdate. He said no, and said that as far as he knew the therapist handled all that for him.

Kurtz then asked him about the CPS hearing to change the findings of CPS about Krawatsky’s alleged abuses. Kurtz, whether mistakenly or on purpose, misrepresented the playdates with the therapist as having happened after the settlement was reached with CPS to downgrade the findings. In actuality the playdates had happened a couple of months before those hearings.

Kurtz asked him if after that hearing and the decision he decided to work with the first alleged victim’s parents to convince his son to make an allegation.

That was immediately objected to and the objection was sustained.

Kurtz then asked him if the first playdate was recorded. The father initially said yes, but then clarified that it hadn’t. He said that the second meeting was recorded. Kurtz then asked him to confirm that there wasn’t a disclosure made at the second meeting, and he said that wasn’t true. Kurtz asked if there was a disclosure on tape why did the mother of the first alleged victim have to talk to his son. At that point there was an objection and it was sustained.

Kurtz then set up the narrative for his next question, saying that the father had initially not wanted to let the first alleged victim’s mother talk to his kid, but eventually allowed it anyway, that the father had his son in his lap when she came in, that she was very intense, getting loud with his kid, and loudly asking him to tell the truth, to say it happened, and things like that.

The father contradicted that narrative (that she had shouted and demanded specific things of his son) and said that she had just asked his son to tell his father what happened and that talking would make him feel better.

Kurtz then asked him if it was true that she said “Isn’t it true that he offered you money to touch his privates?” He said he didn’t remember her saying that (meaning that’s not what he believes she said).

Kurtz then asked him if his son was diagnosed with a seizure disorder in 2015. He said that his son had had a seizure but wasn’t diagnosed with a seizure disorder. Kurtz asked him why his son had been out on powerful seizure meds he’d had a strong allergic reaction to that almost killed him if he didn’t have a seizure disorder. He said it was preventative.

Next the second alleged victim’s mother was called by Ian Richardson. She said she first met K at Shoresh where she first worked as a counselor and then assistant director of Junior Shoresh, and that her relationship with him was just coworkers, not friends per se, but no reason to dislike him.

Her son, she said, the second alleged victim, attended Shoresh from 2014 – 2015, when she worked there. She said that in 2015 he was in the Shoresh lower boys division, which was 6-7 year olds to 10 year olds. That was the summer, she said, that he was expelled from camp because, as she understood it, he was hitting a kid or two. She said she was told about that toward the end of one day by Krawatsky who carried her son over to her, holding him over his shoulder.

She said her son was crying and kicking and not happy when Krawatsky brought him. She said she tried consoling her son, and doesn’t remember her conversation with Krawatsky at that time because she was more concerned with consoling her son.

After camp 2015, she said, she and her husband started noticing behavioral changes in their son. He was bedwetting every day, she said, didn’t want to do things they’d done before, and refused to go into locker rooms.

She said the last time she remembered her son bedwetting was when he was potty trained around 3 years old, and maybe the occasional accident, but it really started again more frequently, eventually stopping a few years later.

She also said that he would occasionally find himself in locker rooms during summer, when they visited a pool, or did sports, and he’d refuse to go in. To this day, she said, he has an issue entering locker rooms.

She said her son eventually disclosed that Krawatsky offered him $100 to touch his penis. She said that the disclosure came during their nighttime routine after he had a bath, got into bed, and they were doing storytime. She said he started talking about camp, and that’s when he disclosed.

She said she made a recording at the time (this is the recording that was played during Krawatsky’s side’s opening statement). This was the first time they were hearing such a disclosure from him, but they had heard about the allegations previously from CPS so it wasn’t a surprise necessarily, but they didn’t know it had happened to him specifically.

She said she recorded it because she wanted to make sure she didn’t miss anything, or for her husband to miss it, and she just wanted to get the truth. She said she wasn’t coaching him, and wasn’t trying to record so she could hand it to CPS or the police, she just wanted to ask him some questions and record it. She had not been trained in forensic interviewing, she said, she was just trying to understand what happened. She said she had no agenda, and wasn’t trying to make him disclose. In fact, she pointed out, at one point he corrected her about something she said.

Moving on to discuss Krawatsky, she said that she had received a video from him of her son at the Shoresh shabbaton. This, she said, was while she was employed at Shoresh, and as she understood it at the time employees weren’t supposed to use their personal phones during camp.

Direct examination ended with her talking about the pool and locker room and explaining that the divisions were sex segregated so the locker room was divided between boys and girls, and when either was swimming the other side would be empty.

Chris Rolle then cross examined her.

He asked her about the nature of her relationship with Krawatsky during her time working at Shoresh, and she said that they were just colleagues not friends. She said she had no concerns about him at the time and assumed he had gone through the screening to be employed there so that he was fit to work there.

He then asked her about the day he carried her son on his shoulder to bring him to her and whether she understood that her child was having difficulties over the summer. She said that it wasn’t the entire summer, just that one time he brought her son to her.

He then asked her if there was an allegation against her son that at camp he’d threatened to touch another kid’s rectum, and she said she didn’t remember that. He asked her about her role as head of the bus stop and she stated her responsibilities – checking every kid got on the bus – after which he asked her if she recalled her son ever having a negative interaction with kids at the bus stop. She said she didn’t remember.

He then asked her about what kind of contact junior Shoresh campers would have had with Krawatsky and she explained that while the lower part of junior Shoresh would have minimal contact, the final year of junior Shoresh was designed to help acclimate the kids to how lower division worked so they spent a lot of time together, thus exposing them to more of Krawatsky.

He asked her about behavioral changes she noticed in her son and when, and she said that she noticed changes starting to happen after summer 2014, and she believes that something happened with Krawatsky that year. She described seeing behavioral issues in his school where she also worked. She emphasized though that she wasn’t made aware of the issues because she was a worker there, but because she was a parent and that it was standard protocol to tell the parents when kids started acting up.

She said she remembered an incident in spring of 2015 where her son caused such a disturbance that the kindergarten had to be emptied.

He then asked her about her son’s seizures and whether he was diagnosed with a seizure disorder shortly after the incident in Kindergarten. She explained that, no, he didn’t have a seizure disorder, rather he’d had one febrile seizure when he was 2 years old, and they had been following with periodic MRIs to see if there were any changes. She said the doctor said there might have been something because he was noticing that her son seemed to be zoning out a little, and as a preventative measure to make sure he didn’t get seizures he gave her son medicine to alleviate it.

She said that this happened in 2015 but that she didn’t remember if it was before or after the playdates at the therapist’s office. Asked about the reaction her son had she said that he had a severe allergic reaction to the medicine, but rather than agreeing that he almost died she said that it was severe and that he was in the hospital for a while.

He then asked her about whether she knew if as a head counselor Krawatsky could ask permission to use his personal phone, and she said she didn’t know. He asked if she didn’t know if he had gotten permission and she said that you’d have to ask him. He asked her if she cared at the time that he was using his phone and she said she didn’t because as a parent she’d asked for updates and that it was pretty common.

Regarding the playdates with the therapist, he asked her if she was involved in setting them up. She said that her husband led on that but that she knew about them. He asked her if she knew that until the playdates her son had denied anything happened, and she said that he had just not disclosed. He asked her to confirm that he hadn’t disclosed several times to CPS, to the therapist, to her, and she said yes.

He asked her if she knew why the mother of the first alleged victim had reached out to her, and she said she didn’t know specifics, but she knew she had texted and wanted to talk about the case and the boys in general. He showed her a document of text records between her and the mother if the first alleged victim and asked again why the mother of the first alleged victim had reached out. She answered that according to what he’d shown her she wanted to talk about her son because their two sons were friends.

She said that the mother of the first alleged victim introduced herself as his mother and said that the social worker (CPS) suggested she reach out and that she was sure the mother of the second victim was as concerned as she was. He asked if she knew what that meant. She answered saying that her husband testified that they didn’t know why CPS was coming to them, and that text with the mother of the first victim happened before CPS contacted them.

He asked her about several further attempts by the mother of the first victim to contact her, mentioning in various texts that she was deeply troubled by what had happened with their sons, or that she heard they were having trouble with the Shoresh rabbis, or that they were the only ones who could understand what she was going through. She said she didn’t respond to any of these texts from the mother of the first alleged victim, but she did agree to have their two sons meet.

She said she didn’t attend the meetings and that her husband did, and that the purpose of the playdates was to get her son to say what had happened. She acknowledged that the mother of the first alleged victim spoke to her son at the second meeting and that before then her son had denied any abuse. He asked her if after the mother of the first alleged victim spoke to her son is when her own son finally disclosed, and she responded to contradict his implication that the disclosure was immediate, instead saying that it was 2 or 3 weeks later.

He then set out a timeline to set up a question: The playdate happened on December 3rd 2015, a while later on the 23rd there was a meeting with her son, the CPS social worker, detective Davies, and that she gave the recording she made of her son’s disclosure to CPS and Davies, and asked her if the reason she gave the recording to them was to get them to come back and do an additional interview with her son. She said she didn’t know.

He asked her if she knew that the second meeting with CPS at the therapist’s office happened, and she said she didn’t know the details, she wasn’t there.

He then set the stage for the jury regarding her son’s disclosure: He gets out of the bathtub doing his nightly routine, and then asks her if her family was at the time living at a hotel because of a severe fire that had required them to evacuate their house. She said that they could have stayed home if they needed to, the structure was still fine, but they decided to go to a hotel. He asked her if they were there during the fire and had to leave the house, and she replied that yes, that’s what people do in a fire, they evacuate the house.

He asks her about the general hullabaloo of it all, that there’s a fire, and fire trucks coming, and they’re evacuating, and it’s a big deal, and she acknowledges that. She says the fire happened Monday before Thanksgiving.

He states that they’re in the hotel in December in two adjoining rooms, and they’re in one of the rooms with their son, and he asks her what he started to say. She said that he started talking about camp – she assumes when she was in bed doing his bedtime routine – and that’s when she reached for her phone. She said she didn’t remember his exact words but when he started talking about camp she started discreetly recording without him noticing so he shouldn’t stop talking.

He starts playing the audio of that recording, the same audio that was played in their opening statement. First snippet he played was about her asking her son if he could tell her the person who hurt her, and if he had hurt anyone else. He asked her why that was her follow up question and she said that she had no training in how to handle a disclosure, she’s just a mom trying to see what happened with her son, and that’s why she asked what she asked throughout the recording.

Next snippet was her asking if her son knew the first alleged victim and he asked if that was her trying to tie that kid in with her own son’s experiences. She said no.

Next snippet is the allegation her son made then that Krawatsky had offered him $100 to touch his penis, and that Krawatsky had hurt him and said mean things. On one detail of it her son corrected her. She then asked if Krawatsky had hurt the first alleged victim as well, and Rolle asked her if she was trying to get her son to corroborate what the first alleged victim had said, and she said no. He challenged her saying that she at that point had known the first alleged victim’s allegations, and she said that this had all been very emotional for her and that her husband had been handling most of it.

Next snippet was regarding her son saying that he had been left alone on his own at some point on the Shoresh Shabbaton. He asked her why she was asking her son about that, and she said that kids shouldn’t be left unattended in camp. He asked if she’d ever heard him say he’d been alone at some point over the shabbaton before this point, and she said no.

Next snippet is her son saying that Krawatsky was rude and mean to other kids and that he knows because people told him. He asked her, referring back to her son being expelled from camp, if by the time this recording was made her son blamed Krawatsky for his expulsion. She said that at the time that was true.

Next snippet was her asking if her son and Krawatsky were ever alone and he said no. Then there were questions played regarding the sleepover at camp. He asked her if she was asking those questions because she thought Krawatsky had abused her son during the sleepover at camp. She said that she was just asking questions with no specific intent to identify a time and place, she just wanted to ask her son about things she knew he had attended. He asked her if the questions had anything to do with theorizing the parents of the first alleged victim may have shared with her, and she said no.

Next snippet was whether Krawatsky was with him at the shabbaton (no) if he saw Krawatsky at all (yes), if Krawatsky scared him, and how many times Krawatsky had asked her son to touch him. He then asked her if she had asked him over and over (implying that she was asking too many times to elicit a specific response). She said no, that they were talking about the shabbaton so she was asking her son if Krawatsky had touched him over the shabbaton.

Next snippet was her asking when the touching happened, and her son responded that it was the middle of the end of camp. She asks her son again about how frequently the touching happened.

Rolle asked her if she was asking so often because she was expecting a different answer, and she said no, that she knows with 7 year olds you have to ask them questions a few times before they answer it.

Next snippet is of her son not wanting to answer any more questions. She asks him a few more questions about what happened, and he says nothing and seems to get a little tired of answering. One of the questions is what her son wants to happen to Krawatsky.

Rolle asked her why she would ask her son such a question and she said because kids are taught at home and in school that actions have consequences.

Next snippet had some more questions about the first alleged victim’s son and if there was anyone else Krawatsky hurt.

Rolle asked why she was mentioning the first alleged victim again. She said it was because their children were close friends and she didn’t know any of the other kids. He asked her if it was because she knew the other kid had a story and she was trying to get another story (to corroborate that one), and she said no.

Cross examination ended, and Ian Richardson asked some redirect questions.

He asked her about the incident when Krawatsky carried her son to her at camp and if anyone else was with him when he was carrying her son to her. She said no. He asked her if the recording was her trying to get the truth, and she said yes. He then asked her if she wanted the truth to be that her kid was abused, and, crying, she responded no.

She was excused and they broke for lunch.