Author’s Note: Here’s the link to the Facebook event for this Sunday’s protest of the Novominsker Rebbe’s, and by extension Agudah’s, rape-enabling policies: https://www.facebook.com/events/261681534310970/

I started off in activism, much in the same way every other activist starts, with a young, optimistic, incredibly naïve idea of what I could accomplish if I tried hard enough. The problem: children were being abused, suffering horribly at the hands of people who violated them in ways that would viscerally incense anyone possessed of a conscience. Surely the problem was one of ignorance. It seemed to me, as it seems to many young, upstart activists, that when apprised of the horrifying reality and pervasiveness of child sexual abuse, people of conscience, people who are otherwise God-fearing fellow Orthodox Jews, couldn’t possibly stand idly by and allow such injustices to continue. No, it must be ignorance, I figured, and ignorance can be educated.

At the time I was confused about my place in the Jewish faith. I’d been raised solidly Charedi in Boro Park, taught from a young age to keep shabbos and kashrus, to daven three times a day, to value torah, and to respect gedolim. Gedolim were the closest thing we had to prophets. They didn’t talk to God, but after a lifetime of devotion to God, the study of Torah, and living piously, living as an example for the rest of us to follow, surely they were the most qualified to tell us what God wanted of us.

But that sort of devotion surely must come at a price, a certain detachment from the mundane, from the day-to-day of our lay lives. It’s no wonder they didn’t do anything about the rampant sexual abuse in their communities, no wonder that when they were handed a case to adjudicate they made the incorrect choice. It wasn’t their fault, they simply didn’t understand the exactly nature of the problem they were adjudicating. They simply didn’t understand what it means for a victim to feel so abandoned, betrayed, and violated by their friends, family, and community that the only apparent way out is suicide. Surely they’d never experienced being in such a mental space.

Surely they’d never been in so much pain that the only way to numb it, to make it somewhat bearable, survivable, was to stay drunk or stay high for long enough to function. Surely they’d never felt so out of control that were compelled to stuff themselves to make themselves feel full of something other than pain only to empty themselves out again with a well placed finger down their throats; surely they’d never felt the need to exert a similar control over something – anything – in their lives by not eating.

No, they couldn’t possibly have experienced these things. And why would they? They were holy, as close to perfect as a human being could be, and God rewards those who follow God’s law so devotedly. It wasn’t their fault that they’d never experienced such pain. They’d worked hard for their rewards. Their lack of perspective wasn’t a flaw, but a testament to their righteousness. Their detachment was both a byproduct and a reward of the lives they’d led.

But surely these paragons, once informed of the pain we were experiencing, once confronted, not adversarially but respectfully, unlike those other activists who were just out to shame them, mock their torah, their communities, and their devotion to both, activists who were simply self-interested, ridiculing people who by contrast made them look like the pleasure-seeking self-justifying sinners they surely were – if they were approached by someone who walked in both sets of shoes, a survivor and a devoted member of their community – surely they’d have to take notice and act to help us.

I started to talk to people about getting me some meetings with the men I’d grown up revering. At the time I’d started writing, but still didn’t have my own blog, so I’d hand my articles to other blogs for publication. In Novemeber of 2012, Avi Shafran wrote an article for Cross Currents titled The Evil Eleventh, in which he responded to a 2006 New York Magazine article by Robert Kolker, which speculated that abuse in the Orthodox Jewish world might be more prevalent than it is elsewhere. Shafran, in his response, contended that since there are no statistics, Kolker’s speculative assertions were an “unmitigated insult to the Judaism,” and likened it, due to his reliance on information obtained by a handful of advocates and survivors, to “visiting Sloan Kettering and concluding that there is a national cancer epidemic raging.”

The rest of his response was a classic example of deflecting by focusing attention on the Jimmy Savile case in England, and engaging in No True Scotsmanism, declaring anyone who would do such a thing ipso facto not a religious Jew, thereby – somehow – making it not our problem.

Respectful as I was of gedolim at the time – many of whom Shafran represented as spokesman for Agudath Israel, and by extension the Moetzes Gedolei Hatorah, and distrustful to the point of disdain, at times, of the advocates and activists involved in the issue of child sexual abuse, I nevertheless wrote a response which I intended to publish on a friend’s blog. I figured, however, that it was only fair to send an advance copy to Shafran for comment before publishing.

After emailing back and forth about the article, it seemed that he agreed with my main points, and that my article, as I had intended to publish it, was unfair. He seemed like someone I could talk to, a reasonable person who genuinely cared about the issue, and, given half a chance, would do what he could to help. I told him I would not publish my response, and we set up a time to talk on the phone.

We ended up talking for four nights over the next two weeks, each conversation lasting a couple of hours. I had prepared notes. I knew I wouldn’t get anywhere on many of the topics I raised, but I figured I’d raise them anyway.

Issues like sex education in yeshivos, acknowledging the harm done – whether anything could be done about it or not – in segregating the sexes until marriage, acknowledging – whether anything could be done about it or not – the problems caused by our general reticence to use proper terminology when discussing physical anatomy or sexuality, refusing to discuss sexuality as a topic, and how much harder it makes discussing non-consensual sexual encounters when even consensual encounters are considered taboo. Then there was the fact that teachers, and yeshiva administrations in general are unwilling to allow students to discuss issues they’re having in their personal lives with faith, with the opposite sex, drugs, depression, etc, without fear of expulsion, and that by the time they reach a yeshiva that does allow such discussion between students and faculty, it’s too late.

Then we moved on to the problems caused by sexual abuse, and the terrible suffering it causes to its victims. I ran him through all the problems, both mental and physical, caused by sexual abuse, some which I’d developed having been abused myself for years.

Throughout all of it, he listened sympathetically, sometimes even empathetically. He acknowledged all of my concerns. He admitted that there were issues with the way our communities raise children, and he acknowledged the damage caused by all of these concerns. I thought I was getting somewhere. I thought, finally someone who’s on my side, who has access to gedolim, who can actually help me change things for the better.

And then we got to the psak.

Shortly following the 2011 Agudah Convention, Shafran posted the following psak on Cross Currents, which operates as Agudah’s de facto blog. The psak was posted by Shafran as an official Agudah statement:

- Where there is “raglayim la’davar” (roughly, reason to believe) that a child has been abused or molested, the matter should be reported to the authorities. In such situations, considerations of “tikun ha’olam” (the halachic authority to take steps necessary to “repair the world”), as well as other halachic concepts, override all other considerations.

- This halachic obligation to report where there is raglayim la’davar is not dependent upon any secular legal mandate to report. Thus, it is not limited to a designated class of “mandated reporters,” as is the law in many states (including New York); it is binding upon anyone and everyone. In this respect, the halachic mandate to report is more stringent than secular law.

- However, where the circumstances of the case do not rise to the threshold level of raglayim la’davar, the matter should not be reported to the authorities. In the words of Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, perhaps the most widely respected senior halachic authority in the world today, “I see no basis to permit” reporting “where there is no raglayim la’davar, but rather only ‘eizeh dimyon’ (roughly, some mere conjecture); if we were to permit it, not only would that not result in ‘tikun ha’olam’, it could lead to ‘heres haolam’ (destruction of the world).” [Yeshurun, Volume 7, page 641.]

- Thus, the question of whether the threshold standard of raglayim la’davar has been met so as to justify (indeed, to require) reporting is critical for halachic purposes. (The secular law also typically establishes a threshold for mandated reporters; in New York, it is “reasonable cause to suspect.”) The issue is obviously fact sensitive and must be determined on a case-by-case basis.

- There may be times when an individual may feel that a report or evidence he has seen rises to the level of raglayim la’davar; and times when he may feel otherwise. Because the question of reporting has serious implications for all parties, and raises sensitive halachic issues, the individual should not rely exclusively on his own judgment to determine the presence or absence of raglayim la’davar. Rather, he should present the facts of the case to a rabbi who is expert in halacha and who also has experience in the area of abuse and molestation – someone who is fully sensitive both to the gravity of the halachic considerations and the urgent need to protect children. (In addition, as Rabbi Yehuda Silman states in one of his responsa [Yeshurun, Volume 15, page 589], “of course it is assumed that the rabbi will seek the advice of professionals in the field as may be necessary.”) It is not necessary to convene a formal bais din (rabbinic tribunal) for this purpose, and the matter should be resolved as expeditiously as possible to minimize any chance of the suspect continuing his abusive conduct while the matter is being considered.

While the first four clauses of the psak may not seem all that objectionable, despite the comparison of “reasonable causes to suspect” determined by mental health and law enforcement professionals to raglayim ledavar determined by average, untrained community rabbis, the fifth clause is what’s truly problematic.

The fifth clause seems to indicate that since the average person is not an expert in what constitutes raglayim ledavar, a rabbi should be consulted in every case, either to establish the presence of raglayim ledavar, or to affirm it. What that essentially means, to most people, is that regardless of whether or not your own common sense tells you that there’s clearly raglayim ledavar, you should consult your rabbi anyway just to make sure.

By then I’d been active long enough in survivor communities to have heard countless stories of survivors who had been browbeaten into silence by rabbis who were either ignorant of the damage caused by sexual abused and therefore felt more sympathy either for the abuser who could potentially face serious prison time, or the abuser’s family who would suffer if their loved one was arrested and publicly charged, or who simply persuaded and pressured survivors into silence because they had a vested interest in protecting the abuser. I’d seen the damage caused by this psak, and I wanted Shafran to address my concerns. Surely we could work something out.

I told him my concerns, and he told me that I had gotten the psak all wrong. That it didn’t actually mandate consulting rabbis in every case. That surprised me, so I asked him for specific examples of cases that would or wouldn’t require consulting a rabbi prior to reporting.

According to Shafran, if someone is the victim of abuse, they obviously have raglayim ledavar, and can report without consulting a rabbi. If someone is the parent or guardian of a child who clearly seems like they were abused, or clearly says that they were abused, then you have raglayim ledavar, and can report without consulting a rabbi. The only situation under the psak, according to Shafran, in which you’d actually have to consult a rabbi, is if a child tells you that something happened, but can’t or won’t elaborate, and you’re not sure what they mean.

While the proper protocol for such a situation is to take the child to a mental health professional for evaluation, this interpretation of the psak as laid out by Shafran seemed damned near reasonable. I was stunned. It actually seemed like a decent compromise, a promising starting point. The psak actually was progress. The advocates were wrong. But why did they have this misconception, and why didn’t Agudah do anything to remedy it?

I asked Shafran, still stunned by what he’d told me, why this psak wasn’t more widely publicized, more publicly explained? Why was this psak, as he’d explained it, not published in mainstream Charedi newspapers, like Yated and Hamodia? Why was Agudah not taking out two-page spreads to both defend themselves against the baseless accusations of angry bloggers, and to make sure that children in the community were protected under this new, progressive psak?

Because we don’t want the laypeople interpreting the psak on their own and misapplying it.

That was the response I got.

But why do community rabbis not know about this psak? How are they expected to make the proper decisions if they don’t even know the framework in which they’re expected to operate? I didn’t get a good answer for this.

Alright, but what about having a dedicated panel that’s publicly known to adjudicate sexual abuse cases, and evaluate whether or not they meet the criteria of raglayim ledavar, a panel that would be accountable for the rulings they’d render?

Well, Shafran explained, firstly such a thing wouldn’t be legal. Secondly, no rabbi would want to be the one to step forward and take the lead on such a thing. It would earn them criticism, and cause conflicts with the institutions they lead or represent, jeopardize their positions, or the financial futures of their yeshivos, and no one would want to accept that kind of responsibility.

What if the gedolim came out publicly and did more to raise awareness? Surely, if they took leadership on this, if they all made the issue front and center as a problem that the frum community needs to tackle head-on, rabbis who wanted to become more proactive in fighting against child sexual abuse would feel more comfortable making themselves available.

It was then that Shafran managed my expectations of gedolim.

They have the same problem. They don’t feel they can take that risk, because they still have to worry about their communities, institutions, and positions.

And right there, at that moment, is when the gedolim lost my faith.

“I don’t understand,” I exclaimed bitterly, “Is the dog wagging its tail, or is the tail wagging the dog?”

After I’d calmed down a little bit, apologized for my outburst, and assimilated this world-shattering piece of information, I got back down to business.

Ok, well, if the gedolim aren’t going to help, what can I do to raise awareness in the community? Could Shafran help me get a foot in the door with some of the frum newspapers and magazines so I could publish articles about abuse, and raise community awareness?

Yated, Hamodia, Mishpacha, Ami, and Zman would never take them, he said.

Not even if they were told to?

No.

So what do I do?

Start at the bottom. Go to the Flatbush Jewish Journal. They’ll be more likely to publish something about sexual abuse, provided its written respectfully, in a way that doesn’t accuse the whole community of complicity. Start there. Work your way up.

Can you call the editor in chief and tell him that you’re sending me along?

No.

Can I tell him you sent me?

No.

(In an email a week later he did offer to let me drop his name in an email to the editor of Flatbush Jewish Journal.)

So after four days of talking, after all the things we’ve agreed upon, after all the concern you showed, you can’t help me with anything? Even this? What have I gotten from this?

“.תפסת מרובה לא תפסת”

I’ve since been disabused of all the misconceptions I’ve had regarding gedolim. I should have known, but all the gedolim I’d tried to get meetings with had already met with survivors, had already heard everything I’d wanted to say to them, and their pain had similarly fallen on deaf ears.

I’ve since lost the illusion I had of gedolim as saintly beings with a holy disconnection from mundane reality. They know. But they’re people. They have self-interest. They have ambition. They like power, and money. They’re the same as everyone else. Nothing greater or lesser. Just regular people in charge of regular institutions. They don’t know God any better than the rest of us do. They don’t have any special insight that we don’t. Their ability to use their sechel isn’t any different from ours. There’s nothing innately special about any of them.

They’re gedolim because they have power. They run powerful institutions. They control powerful amounts of money. They have powerful amounts of influence. That’s it. Nothing special.

I lost a fair chunk of my innocence when I realized this. I no longer had heroes to look up to. I no longer had any paragons of virtue after which to model my life. But I’ve met some. There are people I consider tzaddikim. People who have literally stood between a gun and its intended target. People whose careers and public profiles have suffered tremendously because they refused to budge on their principles. People who have publicly acknowledged their complicity in protecting abusers in the past, but have since publicly taken accountability, apologized unreservedly, educated themselves about the issue, and have become some of the leaders in our cause.

Those are people worthy of respect.

And the key difference between them? They are respected but don’t demand respect. They are beloved but don’t demand love. They don’t command awe. They don’t command worship. They’re not the kind of people who would make you walk backwards out of a room they’re occupying so you don’t turn your back on them. They’re always willing to offer advice if asked, but would never demand that you seek their counsel.

They’re the real gedolim, but they would bristle at the title.

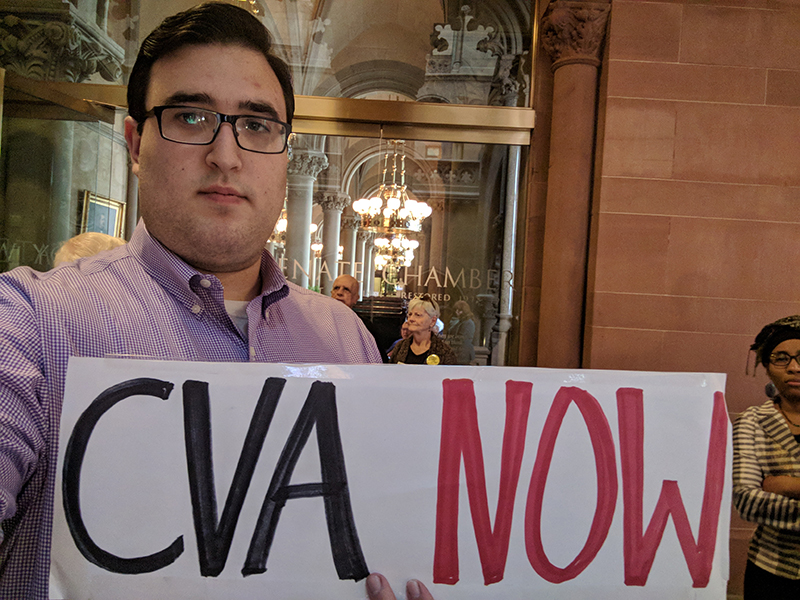

I only came to this realization about gedolim because I came close enough to see their weaknesses. Most people in their communities are too blinded by the mirages they see to recognize these weaknesses. That’s why we’re bringing the issue to the frum community. That’s why ZA’AKAH is protesting outside of the Novominsker Rebbe’s shul. To show the community that we’re not ignoring the issue just because the gedolim tell us to, that the gedolim are not operating in the best interests of our children, but the best interests of the institutions they lead, that there are people out there who see their pain, and care enough to do something about it, and that if they should choose to speak up, we’ll proudly give them a voice.

Join us this Sunday at 3 PM, in front of the Novominsker Shul at 1644 48th street, to protest agudah’s rape enabling policies. Because that’s all their psak does. That’s all Yaakov Perlow accomplished in issuing that psak. By requiring victims to consult a rabbi before reporting child sexual abuse to the authorities, all that’s accomplished is the enabling of coverups by community rabbis either too ignorant, or too biased to make the right decisions.

The only proper response to abuse is reporting to the authorities. And let no gadol tell you otherwise.

Correction: I deleted a sentence saying that Shafran refused to let me drop his name in conversation with Flatbush Jewish Journal. According to my recollection he did refuse during our conversation, but in an email a week later he did recommend that I drop his name in conversation with the Flatbush Jewish Journal. This post has been updated to reflect that change.