Two years ago, following a “Carlebach Shabbos” at my former shul, I wrote an article in which I described the conflict I felt hearing Carlebach being praised for his selflessness and kindness, while simultaneously aware of allegations that he had molested women. I left the article open ended, simply giving my two sides, and left it open for my readers to responded. And boy, did they. The responses flooded in; comments, emails, Facebook messages, even some in-person responses. They came in heavy, heated, and varied. It’s been two years, and I’ve had time to reflect more on the subject, discuss it with more people, and gain some perspective on the issue. Furthermore, since then I’ve spoken to quite a number of his victims, three of whom left comments on my original post. I’d like to address a few things.

Right off the bat, people challenged me on the ethics of sharing an article alleging that someone who is dead and cannot defend himself committed abuse that has never been proven in court. Many people have claimed it’s simply lashon hara, and therefore refuse to even listen. Setting aside whether or not those same people are as careful about the laws of lashon hara when the person under discussion is not one of the spiritual idols, I’ll take it at face value.

It is lashon hara. But one of the exceptions to the prohibitions against speaking lashon hara is when there’s a to’eles, a purpose. Most notably, if there’s a general purpose in the community knowing, if it will prevent some harm, then it is permitted to speak lashon hara. The benefits of discussing Carlebach’s crimes are twofold. First, it sends a message to the community that abusers will have to pay, in one way or another for their crimes, that death is not an escape by which sexual abusers can dodge the repercussions of their crimes; that even if they can’t personally answer for their crimes in life, their legacies will in death. It’s a powerful message to send because there are so many victims out there whose stories are kept hidden by coercion and fear, because the people who keep those secrets are terrified of what their families, their communities might say or do to them if they dare come forward. The more stories are made public, the more people come forward, the more victims will feel safe and secure in coming forward and telling their stories, exposing their abusers, and pursuing justice against them.

Second, for decades Carlebach’s crimes were covered up. For decades, all his victims heard about him was constant praise bordering on deification, any criticism quashed, any attempt at bringing his crimes to light hushed and suppressed. It wasn’t just his followers either who were complicit. Perhaps they can be forgiven because they were blinded by his charisma and façade, but his right-hand men, his gabba’im were aware of the allegations, and actively suppressed the accusers. And for years all his victims heard were stories of Carlebach’s greatness, the constant praise of a man who could do no wrong, simultaneously invalidating their experiences and exalting the man who hurt them. They deserve to have their stories told, to have their experiences validated, and there are enough of them to constitute a to’eles harabim.

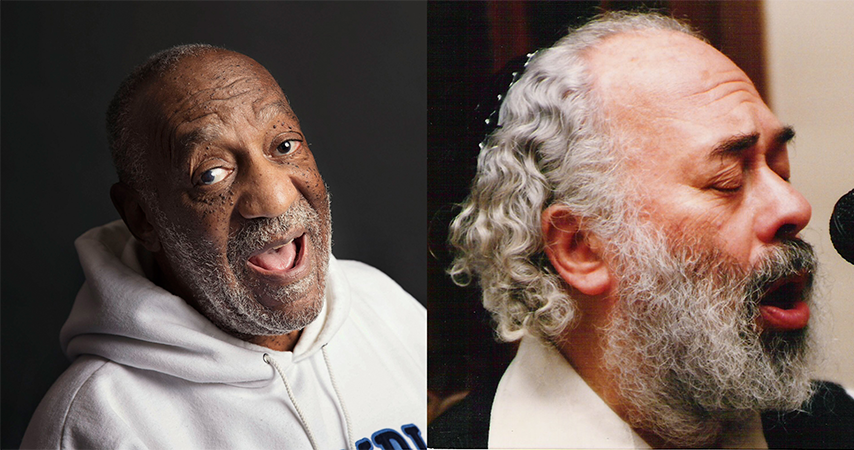

The next thing that bothered people about my article was the comparison to Bill Cosby, a man accused of drugging and raping over 50 women over the course of his life. How could I compare “Reb Shloime,” they asked, to a menuval like Bill Cosby? Carlebach doesn’t stand accused of drugging and raping anyone, just molesting them. And besides, he was a complicated man, everybody knew, nebach, he was probably lonely. It’s nothing like Cosby.

A few things. First, the article was written when the Cosby story was breaking. But more to the point, the comparison is not necessarily to the crimes committed (I’ll get to that in a bit, bear with me), but to the cultural significance of both accusations. Cosby wasn’t just some funny-man any more than Carlebach was just a singer. Both were leaders in their communities. Both had moral messages for their communities, and represented something so much bigger than just the art they each produced. Both were symbols of something greater. And both were accused of just about the most immoral thing a person can do: Violating, in such a heinous and personal fashion, the trust that people had in them and what they represented.

But more importantly, there’s a fundamental misunderstanding people about sexual assault. People assume that if the assault isn’t penetrative, that the trauma isn’t really anywhere near as severe as it would be if the assault were penetrative. Or that if the assault was penetrative, there’s a difference between penetration by a penis, a finger, or a foreign object. That somehow the violation, the trauma, is somehow lesser or more acceptable, or easier to forgive, or easier to do teshuva for simply because the law assigns penalties differently in each case. A sexual assault is a sexual assault, and it is the height of callousness to claim that just because the law needs to make gradated distinctions in penal code in order to actually have a functioning legal system, the trauma is any less severe. Whether penile or digital or with a foreign object, penetrative or non-penetrative, conscious or drugged, sexual assault is a massive violation of a person’s sovereignty over the only thing they really control: their body and their sexuality. Seeing it minimize it in the interest of making one group of people feel better that the guy they revere is not as bad as the guy another group reveres, is disgusting.

This past weekend, after sharing my article again this year in “honor” of Carlebach’s yahrtzeit, two women posted their stories as comments on the article. I’d like to share them below, because it leads me to my final point. The first is by a poster who used the name Shula.

“I was a 15 year old Bais Yaakov girl, enthralled with his music. I was in seventh heaven when he offered me a ride home from a concert. The driver and another person sat in the front, and he sat with me in the back. When he put his arm around my shoulder I was stunned but delighted; and then his hand started massaging my breast. I was 15 and completely naive, had no idea what was happening, but somehow felt embarrassed and ashamed. I just continued to sit silently without moving. This continued until I was dropped off at my house. He told me to come to his hotel room the next morning, and I did! He hugged me very tightly, and I stood frozen, not really understanding what was happening. Then the car came to pick him up, and again I went with him in the car and he dropped me off at school. And I never said a word to anyone, never! I’m a grandmother today, and can still recall that feeling in the pit of my stomach, the confusion and feeling ashamed. I never spoke about this, ever. But all of these comments of denial make me feel I have to confirm that these things happened. He was 40 years old, I was 15. He was an experienced 40 year old man and I was a very naive 15 year old Bais Yaakov girl. In those days we never talked about sex. I had never even spoken to a boy! I didn’t associate him with ‘a boy’ – he was like a parent figure, he was old. But I felt it was something to be ashamed of.

Your article is extremely important – these are conflicts that we have to deal with in life, but if no one ever brings them up, then each person, in each generation, has to over and over again re-invent the wheel of faith. The struggle for faith is hard enough; when these issues are so wrapped in secrecy (and I’m one of those that kept the secret for 53 years!).”

The second was written by a woman who went by the name Jerusalemmom:

“Dear Shula-I had an almost identical story to yours…I was a religious high school girl. 16 years old. I went to his house for a class-his wife opened the door and told me to go downstairs to wait for him. I was the first person there. As I was looking at his incredible library of Judaica he came down-hair and beard wet from the shower. Before I could blink he was on me. One hand down my blouse, another up my dress. I froze in fear. I was so lucky that other people came minutes later for the class and I was “saved.” It has taken me close to 40 years to talk about it. Why bother? People who were his followers give answers like “I can’t believe that” -or “we don’t want to know.” Or “he’s dead and can’t defend himself.”

May g-d grant you peace of mind and may you heal completely. Enjoy your grandchildren and teach them to NEVER EVER let anyone touch them without their permission.”

What’s interesting about Jerusalemmom is that this is the second time she’s shared her story on my blog. The first time she was attacked by Natan Ophir, author of the Carlebach biography, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach: Life, Mission, and Legacy who claimed she was lying. According to him, over the course of his research for his “500 page academic biography” about Carlebach, published in 2014, he had interviewed the women in the Lillith article I quoted in my article, and none of them had stood up to rigorous examination that met his academic standards. I soon found out why.

He started out by asking me to put him in touch with Jerusalemmom. I emailed her and explained to her that Carlebach’s biographer was interested in interviewing her about the claim she’d just made in my comments section for his upcoming biography. I also explained that I got the feeling he’d be adversarial. She asked me for time to think about it, and I went to sleep, expecting to have a response in the morning. The next morning I found a bunch of comments awaiting moderation attacking the veracity of what some unidentified user on my blog had to say in an unverifiable “calumny.” Post after post awaited me in the moderation queue, all of the same kind, along with a slew of emails to my personal account to boot. When Jerusalemmom found out what he was doing, she asked me to remove her comments from my blog, and not contact her again regarding this. I apologized, and removed her comments from the article.

A few days later, the article was posted in a popular feminist Facebook group. Instantly, women started messaging me about their abuse at the hands of Carlebach, and posting comments on the page. Within the hour, Natan Ophir, who just happened to be lurking in that group despite never having participated before, popped up and started attacking anyone in the thread with anything negative to say about Carlebach. He was quickly booted out of the group, not for the comments, but for private messaging several of the women who had left comments on that thread.

In the interest of “fairness,” he sent me the chapter of the book he was writing in Hebrew about Carlebach for review. He said he had included some stories about Carlebach’s “darker side,” which, after reading that chapter, to him meant the claims that he was having contact with women other than his wife. Nothing about the allegations of abuse. When I asked him about it, he claimed he couldn’t find anyone with a sufficiently credible story, despite having spoken to dozens of women about it, one of whom actually confronted him in that Facebook thread about distortions he had made in quoting her in his book.

This all took place in December-January 2014, 20 years after his death. Which leads me to my final point. The third thing people say when these allegations come up is, “Why didn’t these women come forward when it happened? Why are they waiting until he’s dead for twenty years to come forward?” Or, “Oh, it was probably a bunch of women who slept with a celebrity, woke up the next day with buyer’s remorse, and cried sexual assault. You know how it is.” And I’d like to address those claims, because they are worryingly relevant.

The women I spoke to were terrified to come forward publicly. Despite the fact that there’s very little in their lives that they have to lose by doing so at this point. They have families, they’re grandmothers now, for the most part, and they don’t have jobs that hang in the balance if they come out and tell their stories about Carlebach. But they do have to worry about people like Natan Ophir following them around harassing them. They do have to worry about the hatred that Carlebach’s followers seem to have in endless supply for people who have a different, more troubling story about their beloved leader. At this point, many of them feel that it’s just not worth fighting that battle.

But as to why they didn’t come forward sooner? They did. Or rather, they tried. Many of them tried to confront Carlebach about what he did, but when his gabba’im found out about why they wanted to talk to him, they made sure to keep them away. When his followers found out that someone was harboring such an accusation, they made sure to shut them out, and make it plain that they were no longer welcome. The legend they’d built in their minds and their hearts was too big and too fragile to fail. And the truth is it’s not unexpected. Carlebach, to so many, represents the very essence of their Judaism. For many he’s the very reason they have any connection at all, whether spiritual, cultural, or religious, to Judaism. For many, his message of love and acceptance, of connection to God rather than strict observance of a set of laws, of following the spirit to transcend the letter. Without him that message is lost, and without that message they lose their connection.

I feel for such people. I do. And that’s how we return to the original question: Is it possible to separate the art from the artist; the message from the man. Two years ago, when I wrote the article, I didn’t know the answer. But now, to me, the answer is clear. I’ve decided to let it all go. I no longer listen to or sing his music. I don’t feel personally that it’s appropriate to listen to the music and stories of a man whose art gave him the power and status he needed to get away with abusing so many women. I can’t honestly stand at the Amud and sing L’cha Dodi to any of Carlebach’s tunes and feel anything but dirty. I can’t tell myself that God wants my prayers when they come packaged in such poisoned melodies.

I don’t know if that’s the appropriate decision for everyone to make, but that’s the decision I’ve made. But whether people decide to keep listening to and singing his music, or they decide to let it go and find other sources of inspiration, the man and the artist have to die. The legend has to die. Perhaps the message and the music can live on, but not through him. Not through someone who hurt so many people. He doesn’t deserve our praise.