I never realized how complicated my relationship with food was until I moved. I’ve learned a lot since I moved, particularly how messed up my relationship with food is. It started with being able to cook. I was able to cook when I used to live at home, but it wasn’t so simple. Nothing really was. Cooking was a kind of trade-off requiring serious consideration of cost vs benefit. On the one hand I would have yummy food when I finished cooking, but on the other hand, I wouldn’t be safe while cooking. Not emotionally, anyway.

Abuse is insidious in the way it affects your life so completely, ruining even the little things that should be ordinary and routine, performed without thought or consideration of consequences. Like cooking dinner. Like going to the fridge to see what’s in it. Like going to the kitchen to get a fucking banana. It shouldn’t be difficult. It should be something you don’t even have to think about, something you just absently get up and do while engrossed in a show you’re bingewatching on Netflix, or a conversation with your best friend about “oh my god did you see what she was wearing?!?” It shouldn’t require cost-benefit analysis.

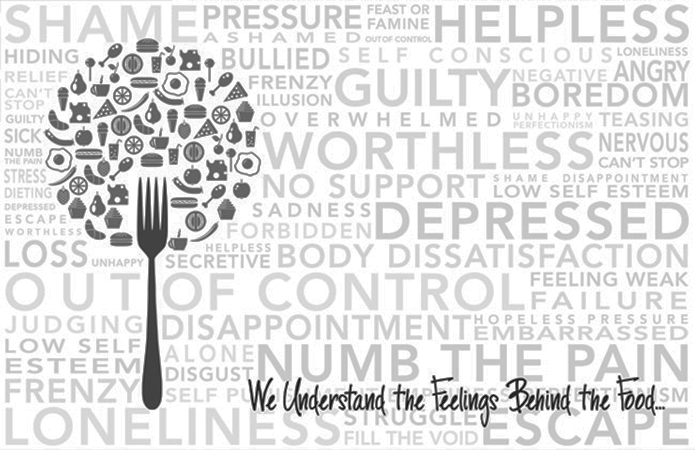

I’m pretty fat. There’s no sugarcoating that. I can already hear people tapping away at their keyboards, typing messages to me telling me I’m handsome, and not to hate my body, and to love myself, and blah blah blah. Save it. I’m not ashamed of it. I don’t hate my body. I do wish it were different, but I’m ok with what it looks like. I don’t think I’m ugly. I’m just fat. Get over it. It’s not because I have a glandular problem, or slow metabolism, or one of a dozen other excuses I could come up with (not to delegitimize people who actually have these problems)—it’s because I eat a lot. But what’s interesting, and what I’m beginning to understand, is why I eat so much.

I’ve been fat for most of my life. It started in third grade for reasons that aren’t really relevant right now. I started significantly gaining weight, however, after my abuse was kicked up a notch. My room was the only safe place for me in the house. My room had a door I could lock, or at the very least barricade if my mother tried hurting me. I spent a lot of time in my room, especially if I was cutting school, which happened more and more as the abuse went on. But locks weren’t a perfect solution. I can’t count the number of times she broke the locks, or broke down my door. Sometimes I would just forget to lock it, and she would get in. Or I left it open to let the cleaning lady in, and my mother would rummage through my stuff while my room was being cleaned. Most of my stuff she wasn’t interested in, but what did interest here were my books and my food.

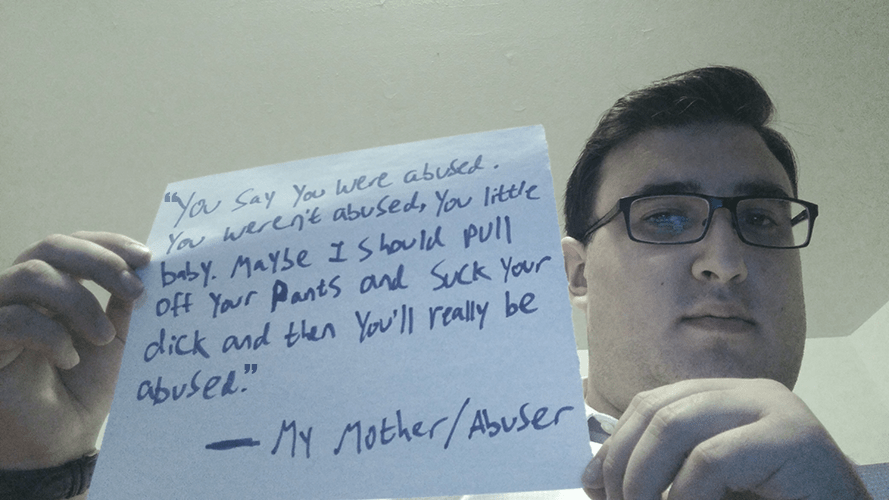

I’ve paid hundreds of dollars in fines to the library because she stole my books and wouldn’t give them back when they were due and couldn’t be renewed because other people had placed holds on them, or because the books were irreparably damaged. My food interested her, not because it was food she couldn’t have gotten from the same grocery I’d gotten mine from, but because the food was mine. Her rationale for stealing my books and my food was that she had given nine months to my gestation, her pain to my birth, and fourteen-odd years to raising me and “giving me everything.” This, in her mind, entitled her to everything that was mine. It entitled her to my food, my books, and my body. It entitled her to abuse me. She took my stuff because it was mine and she believed she was therefore entitled to it as some twisted reparations I owed her as her son.

What this meant, was that the notion of leftovers didn’t exist in my mind, neither did security in the knowledge that I would have food to eat the next time I wanted some. What that meant was that every time I got food, whether it was takeout Chinese, a bag of popcorn, some bagels, a pack of lox, and some cream cheese, or a bag of oranges, I had to eat it all, right then, in one sitting, or at the very least in one day, or it would be gone the next time I wanted it. Of course I could have just ignored the fact that she was stealing from me and just have kept buying more food as I needed it. But it wasn’t the fact that she was stealing from me but the reason why she was stealing from me that made me want to thwart it.

Every time she stole it triggered me. It made me feel unsafe, like I didn’t even have a room, a fridge, a tiny little space that was mine and mine alone, a space in which I had control over my life and my decisions, in which I had some privacy to just be the person I was becoming. It reminded me that I had no control over my life, over my body, that whatever she wanted she could have, and whatever she wanted to do to me she could, because I had no say in my life. It was a complete breach of whatever illusion of security or privacy I had made for myself, and it scared me. So I had to eat everything I bought, regardless of how much it was, or how sick it made me. I had to eat it because eating all of it, even to the point of nausea, still felt better than that feeling of insecurity I felt when she stole from me.

Cooking was a whole other problem. Every time I cooked, she would stand over me, trying to see what I was making, commenting on how it smelled, asking if she could have some. I never responded to her as I had stopped talking to her completely when the abuse got really bad, but what she did was unbelievably triggering to me. I would keep the lid of the pot on, even if I smelled the contents burning, just because I didn’t want her to see what I was making. I wanted something for myself. I wanted some privacy. I wanted there to be something in my life that she wasn’t forcing her way into, and even though this stubbornness was harming me, I needed it. I needed it just for the sake of my sanity. I needed it to feel like a human being.

If I walked away for even a minute—just to pee or get another ingredient—she would run over to the pot, lift the lid, smell it, sample it, and make sure I knew she had. If I didn’t take the pot with me to my room when I ate whatever I had made, she would scrape the dregs out of the bottom of the pot, and then stand outside of my room loudly commenting about it. She would even dig through the garbage if I had thrown something out, either to taste it or to see what I had made. As pathetic as it was to see, it infuriated me and triggered me that she would go to such ridiculous lengths just to impinge on my privacy. Just because she could. Just because she felt entitled to it. To me.

This may seem like a weird power struggle to someone reading this who had the good fortune of being raised by loving parents in a safe environment, but when you’re abused, normal flies out the window. It loses its definition. There’s no such thing as normal. Everything has subtext. Everything has a deeper, manipulative meaning that may not be readily apparent to uninformed observers. Everything means something else. Everything is a power struggle. Everything. Is. So. Fucking. Triggering.

Eating too much was the only way for me to keep my sanity. I couldn’t leave leftovers. If I put something in the fridge, I’d constantly be worrying about it. Cooking food wasn’t a good option either, because it would involve subjecting myself to an hour or more of my mother talking to me, leaning over me, commenting about me, being around me, triggering me. Even going to the fridge to get what was there wasn’t ok for me because it meant she would see me, start talking, and trigger me. I wanted to minimize the time I had to deal with her.

Takeout was the best option. But the thing about never feeling secure in your next meal is that even when you know you can have food whenever you want or need it, it still makes every meal feel like your last. Which meant that even when I ordered takeout, even when I knew I was going to be buying all three meals as I needed them, I’d still buy too much, and would therefore, invariably, eat too much, just to make sure I had eaten enough and wouldn’t be in such desperate need of food if my next mealtime came and for whatever reason I couldn’t get any food.

If I bought takeout, I’d buy two entrees, two sides, a soup, and two sodas, eat it all, and feel like my stomach was coming apart at the seams. Another byproduct of never feeling safe with my food was the speed with which I ate. I’d wolf my food down, which, as anyone can tell you, especially when dealing with large quantities of food, is not healthy. If I bought stuff at the local grocery, I made sure I had more than I needed just to be sure, and then ate all of it. I ate until it hurt. I ate until I felt safe.

I haven’t lived there for 5 months and counting, and I’ve come to realize some things. It started when I got my regular-sized fridge. When I moved into my apartment, my landlady provided me with a wine cooler in lieu of a fridge. It was fine really, because I had brought a minifridge with me. But for the first four months of living there, I didn’t have a freezer, which was not only annoying, but also a painful reminder of the place I’d left. When I lived over there (I’m loathe to call it home), I had eventually bought myself a minifridge—the same minifridge I brought with me when I moved—but it didn’t have a freezer. We had freezers in the kitchen, but I had no way of ensuring that what I put in there would stay there, and I tried my best to keep the time I spent out of my room to an absolutely minimum, so I never bought anything that needed to be stored frozen.

When I finally got my regular-sized fridge, complete with beautiful freezer compartment, it finally felt like I had a normal home—a home that was mine, that I controlled, in which I was safe. I couldn’t place the feeling, but I knew it felt right. This past Thursday night it finally hit me: For the first time in my life I have a fully stocked kitchen, fully stocked refrigerator, fully stocked freezer, and I have control over all of it. It’s completely safe. No one can use it to control me. It’s mine. I finally have control over what I eat, when I eat it, how much of it I eat, and whether or not I want to save some for later.

If I want to make myself dinner, now all it involves is googling a recipe, going over to my cabinet, getting the ingredients, getting stuff from my fridge, cutting it all up, mixing it all together, cooking or baking it at my leisure, all safe from any worry of being triggered, manipulated, controlled, or otherwise made to feel unsafe. It’s no longer a calculation but a reflex. I’m hungry—I make food. I’m full—I stop eating. If there are leftovers, I put it in the fridge. When I want it again, it’s still there. I no longer have to eat the way I used to. I no longer need to feel like my stomach is exploding to feel safe. I no longer have to spend time deciding whether or not it’s worth leaving my room. I’m safe. I’m home. I can eat like a normal human being for the first time in my life and it feels amazing.

Spices feel amazing. Ice cream feels amazing. Putting the container away feels amazing. Leftovers are a miracle. I’ve lost ten pounds in the month since I’ve gotten my fridge and I could not be happier.

It’s still not perfect. I didn’t just magically stop eating too much just because I realized I don’t have to. It’s an ongoing process. Sometimes I have to actually tell myself that I’m safe, that I don’t have to eat anymore, that just feeling satisfied is ok and that I don’t have to eat until it hurts. Sometimes that isn’t enough and I really feel like I need that feeling. I’ve started keeping a gallon of water handy and chugging that until I feel that same fullness. That helps sometimes. Sometimes even that isn’t enough and I still eat like I used to. It’s going to take some time until I get used to this new life, but in the meantime I’m happy that I’ve even come this far.

On the first night of Pesach past, I asked my rabbi if I could say Birkas HaGomel after surviving for so many years where I used to live, including two suicide attempts. He told me that I didn’t meet the halachic requirements, but the blessing encompasses everything I feel, and everything I want to say to God about my life, so here goes: בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם הַגּוֹמֵל לְחַיָּבִים טוֹבוֹת, שֶׁגְּמָלַנִי כָּל טוּב.